Ideal Transformer on Load:

In order to visualize the effect of flow of secondary current in a transformer, certain idealizing assumptions will be made which are close approximations for a practical transformer. A transformer possessing these ideal properties is hypothetical (has no real existence) and is referred to as the Ideal Transformer on Load. It possesses certain essential features of a real transformer but some details of minor significance are ignored which will be reintroduced at a refined stage of analysis. The idealizing assumptions made are listed below:

- The primary and secondary windings have zero resistance. It means that there is no ohmic power loss and no resistive voltage drop in the Ideal Transformer on Load. An actual transformer has finite but small winding resistances. It will also be assumed that there is no stray capacitance, though the actual transformer has inter-turn capacitance and capacitance between turns and ground but their effect is negligible at 50 Hz.

- There is no leakage flux so that all the flux is confined to the core and links both the windings. An actual transformer does have a small amount of leakage flux which can be accounted for in detailed analysis by appropriate circuit modelling.

- The core has infinite permeability so that zero magnetizing current is needed to establish the requisite amount of flux (Eq. (3.6)) in the core.

- The core-loss (hysteresis as well as eddy-current loss) is considered zero.

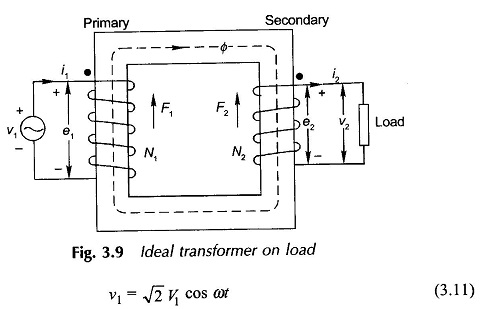

Figure 3.9 shows an Ideal Transformer on Load having a primary of N1 turns and a secondary of N2 turns on a common magnetic core. The voltage of the source to which the primary is connected is

while the secondary is initially assumed to be an open circuited. As a consequence, flux Φ is established in the core (Eq. (3.6)) such that

but the exciting current drawn from the source is zero by virtue of assumption (iii) above. The flux Φ which is wholly mutual (assumption (ii) above) causes an emf

![]() to be induced in the secondary of polarity marked on the diagram for the winding direction indicated. The dots marked at one end of each winding indicate the winding ends which simultaneously have the same polarity due to emfs induced. From Eqs (3.12) and (3.13)

to be induced in the secondary of polarity marked on the diagram for the winding direction indicated. The dots marked at one end of each winding indicate the winding ends which simultaneously have the same polarity due to emfs induced. From Eqs (3.12) and (3.13)

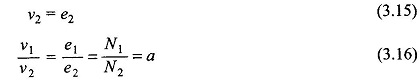

Since a, the transformation ratio, is a constant, e1 and e2 are in phase. The secondary terminal voltage is

Since a, the transformation ratio, is a constant, e1 and e2 are in phase. The secondary terminal voltage is

Hence

It is, therefore, seen that an Ideal Transformer on Load changes (transforms) voltages in direct ratio of the number of turns in the two windings. In terms of rms values Eq. (3.16) implies

Now let the secondary be connected to a load of impedance Z2 so that the secondary feeds a sinusoidal current of instantaneous value i2 to the load. Due to this flow of current, the secondary creates mmf F2 = i2N2 opposing the flux Φ. However, the mutual flux Φ cannot change as otherwise the (ν1,e1) balance will be disturbed (this balance must always hold as winding has zero leakage resistance). The result is that the primary draws a current i1 from the source so as to create mmf F1 = i1 N1 which at all time cancels out the load caused mmf i2N2 so that Φ is maintained constant independent of the load current flow, Thus

Obviously i1 and i2 are in phase for positive current directions marked on the diagram (primary current in at the dotted terminal and secondary current out of the dotted terminal). Since flux Φ is independent of load, so is e2, and ν2 must always equal e2 as the secondary is also resistanceless. Therefore, from Eqs (3.17) and (3.19)

Obviously i1 and i2 are in phase for positive current directions marked on the diagram (primary current in at the dotted terminal and secondary current out of the dotted terminal). Since flux Φ is independent of load, so is e2, and ν2 must always equal e2 as the secondary is also resistanceless. Therefore, from Eqs (3.17) and (3.19)

which means that the instantaneous power into primary equals the instantaneous power out of secondary, a direct consequence of the assumption (i) which means a loss-less transformer.

which means that the instantaneous power into primary equals the instantaneous power out of secondary, a direct consequence of the assumption (i) which means a loss-less transformer.

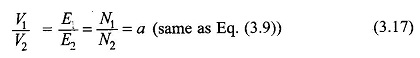

In terms of rms values Eq. (3.19) will be written as

which implies that currents in an ideal transformer transform in inverse ratio of winding turns. Equation (3.20) in terms of rms values will read

i.e. the VA output is balanced by the VA input.

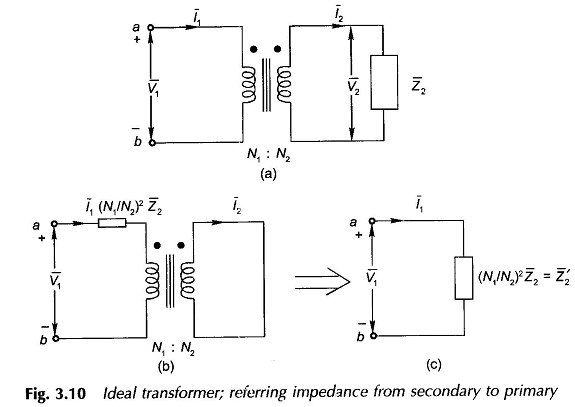

Figure 3.10(a) shows the schematic of the Ideal Transformer on Load of Fig.3.9 with dot marks identifying similar polarity ends. It was already seen above that V1 and V2 are in phase and so are I1 and I2. Now

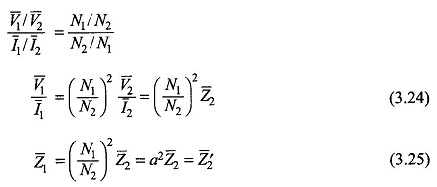

Dividing Eq. (3.23a) by Eq. (3.23b)

It is concluded from Eq. (3.25) that the impedance on the secondary side when seen (referred to) on the primary side is transformed in the direct ratio of square of turns. Equivalence of Eqs (3.24) and (3.25) to the original circuit of Fig. 3.10(a) is illustrated through Figs 3.10(b) and (c). Similarly an impedance Z1 from the primary side can be referred to the secondary as

Transferring an impedance from one side of a transformer to the other is known as referring the impedance to the other side. Voltages and currents on one side have their counterpart on the other side as per Eqs (3.23(a) and (b)).

In conclusion it may be said that in an ideal transformer voltages are transformed in the direct ratio of turns, currents in the inverse ratio and impedances in the direct ratio squared; while power and VA remain unaltered.

Equation (3.25) illustrates the impedance-modifying property of the transformer which can be exploited for matching a fixed impedance to the source for purposes of maximum power transfer by interposing a transformer of a suitable turn-ratio between the two.