Synchronous Machine Operation:

The Synchronous Machine Operation are examined here under conditions of variable load and variable excitation. One of these quantities will be assumed to be held constant at a time while the other will be allowed to vary over a wide range. Further, here too the armature resistance will be assumed negligible. This does not significantly change the Synchronous Machine Operation but leads to easier understanding of the machine operation.

Generating Machine:

Motoring Machine:

Power-angle Characteristics of Synchronous Machine Operation:

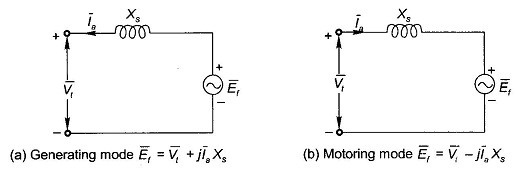

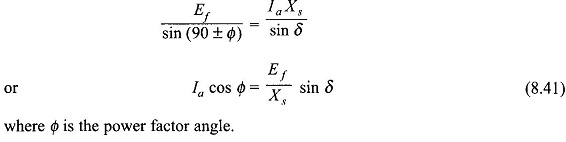

Figure 8.29 shows the circuit diagrams and phasor diagrams of a Synchronous Machine Operation in generating mode (Figs 8.29(a) and (c)) and motoring mode (Figs 8.29 (b) and (d)). The machine is assumed to be connected to infinite bus-bars of voltage Vt. It is easily observed from the phasor diagrams that in generating mode, the excitation emf Ef leads Vt by angle δ, while it lags Vt in the motoring mode. It follows from the phasor triangle OMP (Figs 8.29(c) and (d)) that

Multiplying both sides of Eq. (8.41) by Vt

where

- Pe = Vt la cos Φ = electrical power (per phase) exchanged with the bus-bars

- δ = Angle between Ef and Vt and is called the power angle of the machine (δ has opposite sign for generating/motoring modes).

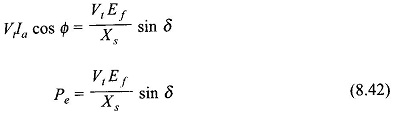

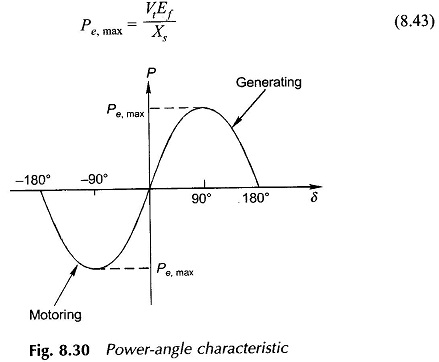

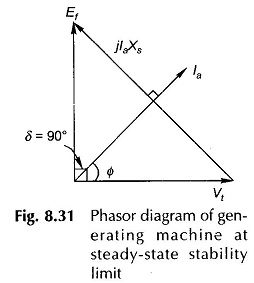

The relationship of Eq. (8.42) is known as the power-angle Characteristics of the machine and is plotted in Fig. 8.30 for given Vt and Ef. The maximum power

occurs at δ = 90° beyond which the machine falls out of step (loses synchronism). The machine can be taken up to Pe,max only by gradually increasing the load. This is known as the steady-state stability limit of the machine. The machine is normally operated at δ much less than 90°. The phasor diagram of a generating machine under condition of Pe,max is drawn in Fig. 8.31. Obviously Ia will be several times max larger than the rated machine current in this condition.

Operation at Constant Load with Variable Excitation:

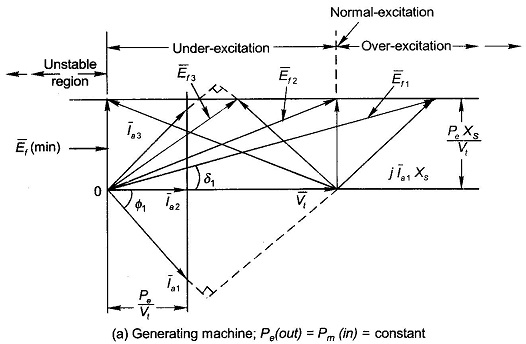

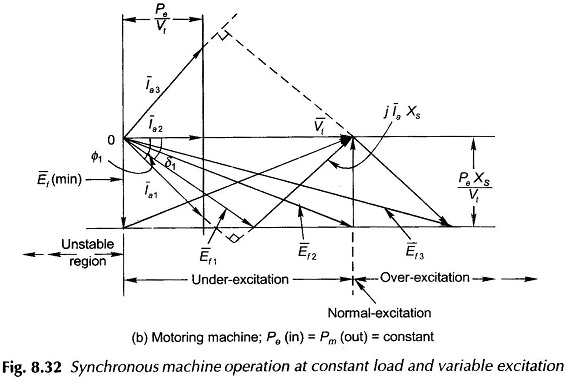

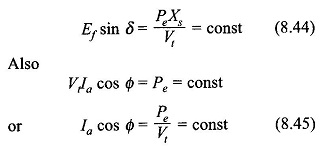

At constant load, from Eq. (8.42)

It is therefore, observed that at constant load, as the excitation emf Ef, is varied (by varying field current If), the power angle δ varies such that Ef sin δ remains constant. The machine behaviour is depicted by the phasor diagrams of Figs (8.32(a) and (b)). As Ef varies, the tip of phasor E̅f moves on a line parallel to V̅t and at distance Efsin δ=PeXs/Vt from it. Since IacosΦ = constant, the projection of the current phasor on Vt must remain constant, i.e. the tip of the current phasor traces a line perpendicular to Vt at distance Ia cos Φ = Pe/Vt from the origin. The current phasor I̅a is always located at 90° to phasor I̅aXs (phasor joining tips to E̅f and V̅t in the direction of E̅f). The excitation (Ef) corresponding to unity power factor is known as normal excitation, while the excitation larger than this is called over-excitation and less than this is called under-excitation. The following conclusions are drawn from the phasor diagrams of Figs 8.32(a)

Generating Machine:

- The machine supplies a lagging power factor current when over-excited.

- The machine supplies a leading power factor current when under-excited.

Motoring Machine:

- The machine draws a leading power factor current when over-excited.

- The machine draws a lagging power factor current when under-excited.

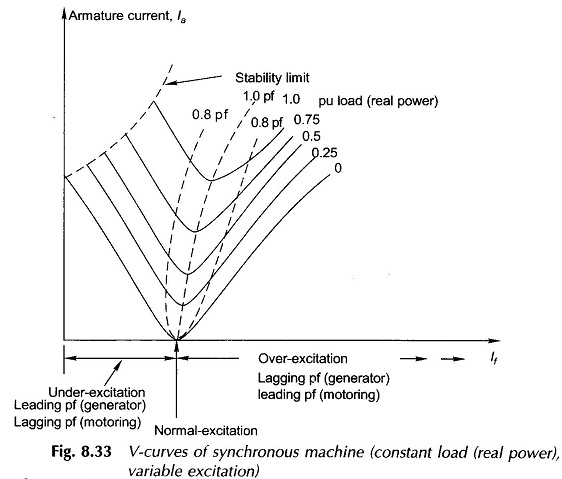

It is also easily observed from these phasor diagrams that the magnitude of the armature current exhibits a minimum when its excitation is continuously increased from an under-excited state. The nature of la versus excitation (If) plot for various values of load (real power) is shown in Fig. 8.33. These are known as V-curves of synchronous machine by virtue of their shape. Though only one figure is drawn for generating/motoring operation, the actual shape of V-curves for the two cases will not be identical. A little reflection will show that PF versus If plots will be inverted V-curves.

Minimum Excitation:

From Figs. 8.32(a) and (b) it is seen that as excitation is reduced, the angle δ continuously increases. The minimum permissible excitation, Ef (min), corresponds to the stability limit, i.e. δ = 90°. Obviously

Minimum field current and corresponding armature current for a given pu load at the limit of stability is indicated by the dotted curve in Fig. 8.33.

Observation:

In a Synchronous Machine Operation the real electrical power exchanged with the bus-bars is controlled by the mechanical shaft power irrespective of excitation. The excitation, on the other hand, governs only the power factor of the machine without affecting the real power flow. For example, in a generator if it is desired to feed more real power into the bus-bars the throttle must be opened admitting more steam into the turbine (coupled to generator) thereby feeding more mechanical power into shaft. As a consequence the power angle δ increases and so does the electrical power output (Eq. 8.42)). However, if it is desired to adjust the machine power factor, its excitation should be varied (well within the limit imposed by Eq. (8.46)).

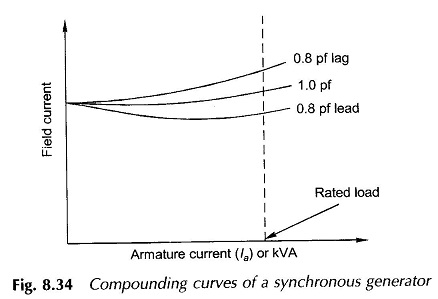

Compounding Curve:

The dotted curves of Figure 8.33 pertain to constant terminal voltage, constant power factor Synchronous Machine Operation. For a generating machine operation these curves are called compounding curves. These are presented once again in Fig. 8.34 as the field current needed for a given armature current or kVA loading at a particular power factor for constant terminal voltage. These are useful guide for generator operation in a power house.

Synchronous Condenser:

It has been seen above that a synchronous motor under over-excited condition operates at a leading power factor. Synchronous motors are therefore employed in large power installations for improving the overall power factor of the installation.

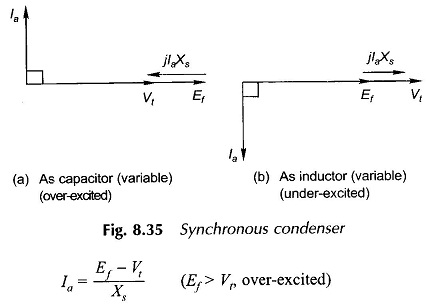

At no-load with losses assumed negligible, a Characteristics of Synchronous Machine Operation at

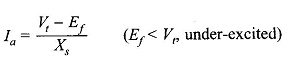

which means that Ef and Vt are in phase. It is seen from the phasor diagram of Fig. 8.35, that the machine (motor) draws zero power factor leading current

and draws zero power factor lagging current

Thus a synchronous motor at no-load behaves as a variable condenser or inductor by simply varying its excitation. The machine operated under such a condition (motor on no-load or light load) is known as a synchronous condenser and finds application in large integrated power systems for improving the power factor under heavy-load conditions and for deproving the power factor under light-load conditions, thereby controlling the voltage profile of the power system within reasonable limits.

Dual-purpose Synchronous Motor:

Synchronous motor is used in an industry/factory for serving two purposes. It drives a constant speed mechanical load such as a large pump, a dc generator, etc. and at the same time it also corrects an otherwise low lagging pf of the electrical load such as induction motors and fluorescent tubes. Such a synchronous motor serving dual-purpose is called dual-purpose synchronous motor.